Parenthesis - defining the structure of Clojure codeλ︎

Clojure uses parenthesis, round brackets (), as a simple way to define the structure of the code and provide clear and unambiguous scope. This structure is the syntax of symbolic expressions.

Parenthesis, or parens for short, are used to define and call functions in our code, include libraries and in fact any behavior we wish to express.

Clojure includes 3 other bracket types to specifically identify data: '() quoted lists and sequences, [] for vectors (arrays) and argument lists, {} for hash-maps and #{} for sets of data.

No other terminators or precedence rules are required to understand how to read and write Clojure.

The Parenthesis hangupλ︎

Some raise the concern that there are "too many brackets" in Clojure.

Clojure doesn't require any additional parens compared to other languages, it simply moves the open parens to the start of the expression giving a clearly defined structure to the code

With support for higher order functions, functional composition and threading macros, Clojure code typically uses fewer parens than other languages especially as the scope of the problem space grows.

All languages use parens to wrap a part of an expression, requiring additional syntax to identify the boundaries of each expression so it can be parsed by humans and computers alike. Clojure uses a single way to express everything, homoiconicity, where as most other languages require additional syntax for different parts of the code.

Using parens, Clojure has a well defined structure that provides a clearly defined scope to every part of the code. There is no requirement to remember a long list of ad-hoc precedence rules, e.g. JavaScript operator precedence.

This structure of Clojure code is simple to parse for both humans and computers. it is simple to navigate, simple to avoid breaking the syntax of the language and simple to provide tooling that keeps the syntax of the code correct.

After realising the simplicity that parens bring, you have to wonder why other (non-lisp) languages made their syntax more complex.

Working with Parensλ︎

Clojure aware editors all support structured editing to manage parens and ensure they remain balanced (same number of open and close parens).

A developer only needs to type the open paren and the editor will automatically add the closing paren.

Parens cannot be deleted unless their content is empty.

Code can be pulled into parens (slurp) or pushed out of parens (barf). Code can be split, joined, wrapped, unwrapped, transposed, convoluted and raised, all without breaking the structure.

- Smartparens for Structural editing - a modern update of ParEdit

- The animated guide to ParEdit

Homoiconicity and Macrosλ︎

Clojure is a dialect of LISP and naturally was designed to be a homoiconic language. This means the syntax for behavior and data is the same. This greatly simplifies the syntax of Clojure and all LISP style languages.

The Clojure Reader is a parser that reads in data structures as expression, rather than parsing of text required by other languages. The result of parsing is a collection of data structures that can be traversed (asymmetric syntax tree - AST). Compared to most languages the compiler does very little and you can consider Clojure really does not have a syntax.

Code is written as data structures that are accessible to the other parts of the code, providing a way to write code that manipulate those data structures and generate new code. In Clojure this type of code is called a macro, a piece of code that writes new code.

None of this would work as simply as it does without using parens and the symbolic expression syntax.

- Inspired by Beating the Averages by Paul Graham

Example: Function invocationλ︎

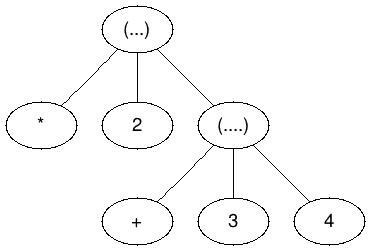

The choice was made early in the design of Lisp that lists would be used for function invocation in the form:

The advantages of this design are:

- a function call is just one expression, called a "form"

- function calls can be constructed (cons function-symbol list-of-args)

- functions can be arguments to other functions (higher order functions)

- simple syntax to parse - everything between two parentheses is a self-contained expression.

- fewer parens due to high order functions, composition and threading macros

The function name could have been put outside the parentheses:

This design has many disadvantages:

- a function call is no longer a single form and have to pass the function name and the argument list.

- syntax is complex and requires additional syntax rules to define a function call

- code generation is very complex

- same number of parens as Clojure or possibly more (no direct support for higher order functions)